12 March 2022

Women's History Month: Catherine Booth

Emily Bright interviews Cathy Le Feuvre

Catherine Booth, who founded The Salvation Army with her husband William, pioneered a radical approach to social action and female equality. To mark International Women’s History Month, Cathy Le Feuvre, author of the biography William and Catherine, speaks to Emily Bright about Catherine's legacy.

Catherine Booth had strong beliefs right at the beginning,’ says Cathy Le Feuvre.

‘She had a strong sense of animal rights. It’s said that she decided from an early age that she wasn’t going to have sugar, because it was a product of the slave trade. She was also a member of the temperance movement, which encouraged people not to drink alcohol because of the risk of alcoholism and people drinking away all their money.’

The driving force behind Catherine’s decisions in her life was, says Cathy, her belief in God.

Catherine was born in 1829 and ‘had a well-formed faith from a young age’. Cathy says: ‘There’s lots of evidence that she went to church when she was growing up. It’s reckoned by the time she was 12, she’d read the Bible several times over.’

It was because of her faith that Catherine met William Booth in 1852, through the Reformed Methodists movement. They married in 1855, and she became a stalwart of spiritual guidance and emotional support to him.

Cathy, whose book is based on their love letters, explains: ‘They were kindred spirits. They both had this deep yearning to see people become Christians. God came first in their lives, even before each other. It was an equal partnership and they spoke about everything.’

Cathy elaborates on what drew William to Catherine.

‘First and foremost, I think he admired her faith. She was living her life for God. William later appreciated her as a wife and as a mother to their eight children. He was also inspired by the way she inspired others, and he admired her intellect and bravery.’

One of Catherine’s acts of bravery was to pioneer the path for female preachers at a time when the idea was widely derided. In 1859, she wrote an article entitled ‘Woman’s Right to Preach’ to set out her theology. She later decided to practise what she preached.

‘In January 1860, she suddenly felt she had to stand up during a meeting,’ says Cathy. ‘She beckoned to her husband, and he bent down and spoke with her before telling the congregation: “My wife would like to say a word.”

‘That was the first time that she’d spoken to a congregation. Then that evening she actually preached. She became recognised as a very strong preacher and had a ministry in her own right.’

Catherine also attracted a different demographic from her husband. Cathy says that she ‘became well known amongst upper-class circles. She talked really well to women about the things they were concerned about. And she reinforced the message “you’re as good as men” without taking anything away from men.

‘That filtered into The Salvation Army, when it was created in 1865. Women quickly became preachers and corps officers.’

Indeed, three of Catherine’s four daughters became leaders in The Salvation Army.

The couple’s evangelistic style grew in popularity. So on 2 July 1865, when William was preaching in the open air, The Christian Mission, as The Salvation Army was formerly named, officially began. Over time, it drew elegant women and reformed alcoholics alike to its ranks.

While their primary aim was to preach the gospel, Catherine and William quickly realised that they had to meet people’s material needs too.

So they went on to establish a pioneering free labour exchange, alongside food banks, soup kitchens, shelters for women fleeing domestic abuse and prostitution, shelters for people experiencing homelessness, and work among prisoners.

In 1890, William published a social action manifesto summing up their life’s work. The book In Darkest England and the Way Out offered a blueprint of how to tackle social ills, spanning topics such as job centres, refuges for women and access to banks and lawyers for people living in urban poverty. On its first day in print, it sold 10,000 copies.

The book’s success was tinged with sadness. It was published two weeks after Catherine had died of breast cancer. However, as Cathy explains, her influence was present on every page.

‘Even in her final days, when she was very ill with cancer, she insisted that William carry on writing. She saw it as their life’s work. The things they’d talked about and the campaigns they’d had were all in there.’

Catherine had gained behind a remarkable reputation as ‘the Army mother’, as Cathy explains.

‘After her death, the Methodist Recorder paid tribute to her as “the greatest Methodist woman of this generation”. About 50,000 mourners from all walks of life processed past her coffin over a five-day period.’

Cathy sums up Catherine Booth’s legacy: ‘She was ahead of her time and had the courage of her convictions. She wasn’t afraid to challenge the social norms of the day, in terms of the place of women.

‘Catherine Booth was one of the pillars of helping women to understand that they had a place in the world. She was inspiring, not just for her own generation, but for future generations. Without her, The Salvation Army wouldn’t be what it is today.’

- William and Catherine is available to buy as a paperback and e-book

Interview by

Emily Bright

Staff Writer, War Cry

More from War Cry

All online articles

A journalist's view: Celebrities are 'just like the rest of us'

After encountering some of the world’s most famous people, journalist Cole Moreton explains what he has learnt about the value of human connection.

Losing a partner: 'My faith has made the tragic turn of events bearable'

Louise Blyth explains how she and her husband found a new outlook after he developed the cancer that would end his life.

'Redeeming Love': From steamy romance to Christian fiction

Author Francine Rivers tells Emily Bright how becoming a Christian prompted her to turn over a new leaf in her career.

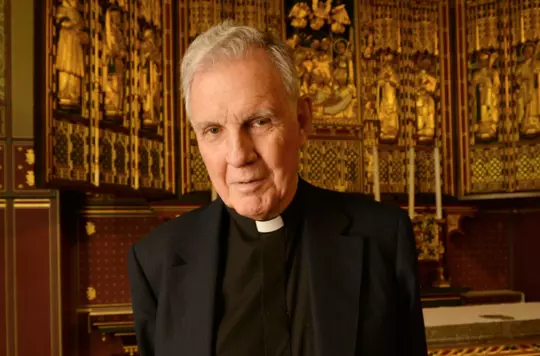

From cabinet minister to prisoner and now prison chaplain

Philip Halcrow interviews Jonathan Aitken and fellow ex-prisoner Edward Smyth about their spiritual survival guide 'Doing Time'.