6 April 2023

Easter: How is the date calculated?

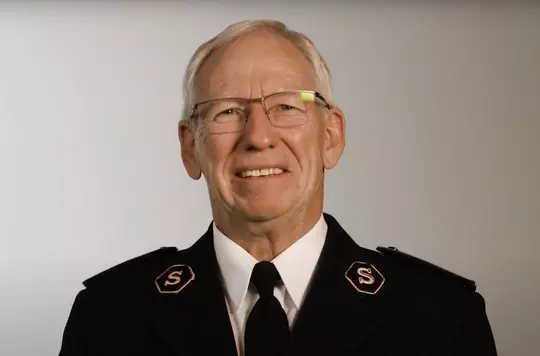

Philip Halcrow

War Cry's Philip Halcrow talks to historian Dr Michael Carter about the timing of Easter.

Whereas Christmas Day falls on 25 December every year, Easter moves around in a way that may be baffling to many people – but not to Dr Michael Carter. Michael is a senior properties historian at English Heritage, which cares for more than 400 buildings, monuments and other locations, including one site that played a major role in the story of how the date of Easter came to be determined in these islands.

‘We know from the Gospels that Christ’s crucifixion and resurrection happened around the time of the Jewish festival of the Passover,’ he says.

‘Passover is determined by the cycles of the moon. In the fourth century, just after Christianity had gained toleration within the Roman Empire, the early Christian Church agreed that Christ’s resurrection must be celebrated on the first Sunday following the first full moon after the spring equinox. So Easter is based on the cycles of what is called the “paschal moon”.’

However, there was some disagreement about how to make the calculations.

‘And,’ Michael says, ‘it got complicated for the Church, especially in seventh-century England.’

He explains: ‘In the fifth century, Germanic peoples – the Anglo-Saxons and Jutes – invaded and settled in what had been the Roman province of Britannia. These Germanic peoples didn’t share the Christian beliefs of many people in late Roman Britain, who were subsequently pushed to the western fringes of the British Isles. Starting in the sixth century, there were efforts to convert the peoples of Anglo-Saxon England to Christianity.’

One such mission began with the arrival in Kent in AD597 of the monk Augustine, who had been sent by Pope Gregory the Great.

‘He established a monastery on the edge of Canterbury and other sites. The monks spread out and in about 620 they arrived in Northumbria, which was the dominant kingdom of Anglo-Saxon England.

‘A parallel but separate programme of evangelisation had also started from the Irish monastery of Iona, off the western coast of Scotland, and those missionaries arrived in Northumbria about the same time.

‘It’s important to emphasise that the Roman and the Hiberno-Scottish missionaries shared the same fundamental beliefs. There was a lot more that united them than divided them. But one of the biggest differences was how to calculate the date of Easter, even though the formula that the Irish missionaries had adopted was no longer being used in the rest of Ireland.

The differences were highlighted in the life of the King and Queen of Northumbria, as recorded shortly after events by the historian Bede.

Michael explains: ‘King Oswiu was a recent convert to Christianity and followed the Irish tradition. His wife, Eanflaed, was from Kent and followed the Roman traditions. Bede tells us that one year, the different ways of calculating Easter led to a scenario where the king was happily celebrating Easter while the queen and her household were still observing their Lenten fast.

‘Something had to be done. So Oswiu called a meeting of churchmen and nobles to agree on the timing of Easter once and for all.’

The resulting debate was held in 664 at a site that will be visited by holidaymakers over the Easter weekend: Whitby Abbey.

‘The meeting became known as the Synod of Whitby,’ says Michael. ‘It took place at the monastery of St Hild.’

Michael describes what took place: ‘Colman, who is Bishop of Lindisfarne and effectively the court bishop for Oswiu, presents the Irish case. Then Wilfrid, a local boy who is abbot of Ripon, forcefully presents the Roman case.

‘They both appeal to apostolic tradition. Colman says he is speaking from the tradition of St John the Evangelist, which has been mediated to him via St Columba. Wilfrid says he is speaking from the apostolic tradition of St Peter. And he quotes the words that Christ said to Peter: “You are Peter and upon this rock I shall build my Church.”

‘It’s a slam dunk. Oswiu turns to Colman and asks whether he can cite a similar authority. Colman has to say that he can’t.

‘Then Oswiu, fearful of appearing at the gates of Heaven, for which traditionally St Peter has been given the keys, says that, lest he does not gain admittance, he is siding with Wilfrid and his Roman tradition.

‘The king’s decision seems to have been accepted, except by Colman and a few of his adherents.

The subject of the timing of Easter continued to be discussed in some quarters – and still is – but Michael says it is interesting that ‘this unity of observance in England at the Synod of Whitby endures to this day. Even when England breaks away from the Pope in Rome in the 16th century, there’s no question of reverting to a different calendar for calculations about Easter.’

Christmas may have turned into what perhaps can be seen as the most universally joyful festival, but, from a Christian perspective, it looks significant only because of the events marked at Easter.

‘In late medieval devotional meditations on the life of Christ,’ says Michael, ‘they start with the Annunciation and the Nativity and they go all the way through to the Passion, the Resurrection and then the Ascension – and it’s all seen as being part of the one story. The story is about Christ’s death, his sacrifice on the cross, and then his triumph over death, offering humanity the chance of eternal life.’

It’s why Easter – whenever it falls – is, as Michael says, ‘the most important Christian festival of the year’.

Written by

Philip Halcrow

Deputy Editor, War Cry

Discover more

Devotions, articles and resources to help you journey through Lent and celebrate Easter.

Ivan Radford explores portrayals of Jesus and the events of Easter on film and TV.

Major Malcolm Martin considers the conflict of opinion about Jesus.